This is a traditional house seen in Parsma. The open veranda is possibly early 20th century and the rest of the building is most likely much earlier .

This is a traditional house seen in Parsma. The open veranda is possibly early 20th century and the rest of the building is most likely much earlier .This is a tough subject for me since I can only recount what I’ve observed on my travels and subsequently gleaned from fellow travellers and my family. Please contact me if you know of any information I've provided is incorrect.

This beguiling region is largely made from a small Hamlets where the dwellings are of constructed from wood and stone. Peppered around the landscape are fortified towers and in some villages such as Parsma ,imposing fortresses from a distant age can be found.

Most of the scholarly accounts concentrate on the towers and fortresses. These edifices, poised like sentinels across Tusheti peer down the valleys, watching time slowly slip by as we hurtle into the twenty first century.

I would like to focus first on the vernacular homes built by the Tush. To my mind these humble buildings are as equally exciting as the statuesque towers and continue to hold their own equally fascinating secrets of the past.

One of my favourite examples of a two story house built in the late 1900's in Shenako

One of my favourite examples of a two story house built in the late 1900's in ShenakoBy the end of 19th century domestic architecture for the Tush had evolved into a house with balcony, including ornamental work such as decorated doors and windows with fretwork balconies. A prime example being the decorative fretwork found on the balcony, probably dating from the early 20th century. Unfortunately this fretwork is not a local vernacular but a feature taken from the merchant homes to be seen in cities such Tbilisi ,as is much of the detailing .I'm told this is most likely influenced by houses at that time seen in Telavi although many of these examples are no lost.

These are typical merchant houses to be seen in Tbilisi. I think I prefer the Tusheti version of the balcony detail.

These are typical merchant houses to be seen in Tbilisi. I think I prefer the Tusheti version of the balcony detail.  A magnificent balcony detail to be seen in Upper Omalo.

A magnificent balcony detail to be seen in Upper Omalo.  I thought this balcony illustrates the eclectic style to be seen in villages such as Shenko, with iron railings and terrific fretwork.This type of detailing would have been created over a period of time with improvements made when the cash was availble .

I thought this balcony illustrates the eclectic style to be seen in villages such as Shenko, with iron railings and terrific fretwork.This type of detailing would have been created over a period of time with improvements made when the cash was availble .

The man in the foreground is one of the oldest men in Shenako.

Homes in Tusheti are largely built from dry construction with slate walls supporting both the floor joists and rafters. Similar construction can be seen in the mountainous region of southern Bulgaria such as the village of Dolen. The first floor in the contemporary style (I’m sorry if you are American and are getting confused at this point, in England we call the first floor what you would call the second floor) often reveals a wooden terrace or balcony contained by slate walls with large stone slates on the roof .

Homes in Tusheti are largely built from dry construction with slate walls supporting both the floor joists and rafters. Similar construction can be seen in the mountainous region of southern Bulgaria such as the village of Dolen. The first floor in the contemporary style (I’m sorry if you are American and are getting confused at this point, in England we call the first floor what you would call the second floor) often reveals a wooden terrace or balcony contained by slate walls with large stone slates on the roof .

Scene over some classic roofs in Shenako.

Scene over some classic roofs in Shenako.  An excellent example contributed by Kakha Khimshiashvili

An excellent example contributed by Kakha Khimshiashvili This can be pitched on either one or two sides but most commonly two. The Tush started to construct this type of housing from the mid 19th century when life in Tusheti became less treacherous and the chances of marauding tribes from across the boarders were diminishing.

For me a good example of the late 19th century style can be found in Shenako where the village was totally rebuilt after a plague hit the old village, leaving the survivors to build their new homes out of reverence for their dead on a site nearby. Here the principle of the balcony is most prevalent. Much of the timber work is highly decorated and remnants of brightly covered decoration can still be found on many of the homes.

This Shenako balcony demonstrates how colour was used in a previous era. It must have look wonderful in it's day.

This Shenako balcony demonstrates how colour was used in a previous era. It must have look wonderful in it's day. These homes were built as the winter quarters in Shenako. Often built with mud and cow dung render and on rare occasions I beleive lime mortar render has been used but this has not been varified . These homes lack the fortifications see in other areas and I've not seen quite so much render on other homes .

These homes were built as the winter quarters in Shenako. Often built with mud and cow dung render and on rare occasions I beleive lime mortar render has been used but this has not been varified . These homes lack the fortifications see in other areas and I've not seen quite so much render on other homes . As with many of the homes in Tusheti , the ground floor is dedicated to stock while the family lives on the first floor. The open rafters are used to store dry goods .

As with many of the homes in Tusheti , the ground floor is dedicated to stock while the family lives on the first floor. The open rafters are used to store dry goods . Upper Omalo had nearly fallen into total disrepair but now the village is undergoing a rebirth. Here are some excellent examples of late 19th century construction built around homes from an earlier era.

Upper Omalo had nearly fallen into total disrepair but now the village is undergoing a rebirth. Here are some excellent examples of late 19th century construction built around homes from an earlier era.At the other end of the Pirikiti valley you will find examples of the early construction. Single story homes hugging the ground to keep the hostile winters at bay. The windows in these homes are very small ,similar to the crofts found in Scotland.

This image illustrates the older style of construction ,pre late 19th century in Parsma .Often but not exclusively single story buildings clustered tightly together.

This image illustrates the older style of construction ,pre late 19th century in Parsma .Often but not exclusively single story buildings clustered tightly together. In other parts of Tusheti one can find homes built on the principle of a fortress. In such instances the buildings can reach five stories high. I can only think these buildings grew over time to contain the extended family .

This view looking down on the village of Dochu illustrates some of the taller homes to be found in Tusheti. I imagine the balconies clinging to the side of these fine buildings area recent addition . I spent a night in Dochu with my family in 2007 and found it amusing to observe the villages spying each other with their binoculars. In the summer 2008 we spend a couple of days in Gogurlta on the opposite side of the gorge. They also kept an eye on their distant neighbours with binoculars.

This view looking down on the village of Dochu illustrates some of the taller homes to be found in Tusheti. I imagine the balconies clinging to the side of these fine buildings area recent addition . I spent a night in Dochu with my family in 2007 and found it amusing to observe the villages spying each other with their binoculars. In the summer 2008 we spend a couple of days in Gogurlta on the opposite side of the gorge. They also kept an eye on their distant neighbours with binoculars. If you are familiar with the buildings in Leshten and Kovachevitsa in Bulgaria you will see an uncanny similarity.

Another view of Dochu and their magnificent buildings . Far off in the distance you can make out Gogurlta. The ruined building in the foreground is a derelict tower with the roof missing.

Another view of Dochu and their magnificent buildings . Far off in the distance you can make out Gogurlta. The ruined building in the foreground is a derelict tower with the roof missing. This picture of a number of houses in Dartlo demonstrates typical Tusheti towers in the background sitting within the village settlement.

This picture of a number of houses in Dartlo demonstrates typical Tusheti towers in the background sitting within the village settlement.

This fortress style home can be see in Iliurta where one of two Tusheti churches still remain. The strange stick appearing from the roof is a makeshift aerial . You can just see the balcony to the left. A perfect vantage point to see visitors arriving up the trail approaching the village .

This is a rare example of a woven birch batten wall to be seen in Upper Omalo. I understand other examples can be found in Shatili -Khevsureti region

This is a rare example of a woven birch batten wall to be seen in Upper Omalo. I understand other examples can be found in Shatili -Khevsureti region Many of the 19th century buildings have simple additions such as this lean-to. A kitchen and dinning room combined . Notice the abundance of stock fencing to keep the chickens out.

Many of the 19th century buildings have simple additions such as this lean-to. A kitchen and dinning room combined . Notice the abundance of stock fencing to keep the chickens out.  This classic Tusheti farm house is to be found high in the mountains in Gogurlta. The ground floor is used for stock, open rafters to dry crops. A terrace on the front on the living quarters and I expect to the right sits the dairy.

This classic Tusheti farm house is to be found high in the mountains in Gogurlta. The ground floor is used for stock, open rafters to dry crops. A terrace on the front on the living quarters and I expect to the right sits the dairy. Roofs in Tusheti are traditionally made from large natural slates, however these often leak so with the advent of the steel panels many of the slate roofs have been replaced. In some cases the slate has been replaced on top of the steel panel due to the slates weight, essentially keeping the panel in place. This is especially important when violent storms occur in the winter and the wind rips off the gutter edge of the panels . In some instances blue polythene is used as the water proof layer .

Roofs in Tusheti are traditionally made from large natural slates, however these often leak so with the advent of the steel panels many of the slate roofs have been replaced. In some cases the slate has been replaced on top of the steel panel due to the slates weight, essentially keeping the panel in place. This is especially important when violent storms occur in the winter and the wind rips off the gutter edge of the panels . In some instances blue polythene is used as the water proof layer .  Tin houses are not uncommon in Tusheti especially with the more recent construction . Omalo is almost totally built in this manner. The home here is to be found in Dartlo.

Tin houses are not uncommon in Tusheti especially with the more recent construction . Omalo is almost totally built in this manner. The home here is to be found in Dartlo. This tin home is where we stayed in Parsma in the summer of 2008. The view was spectacular and the home very comfortable.

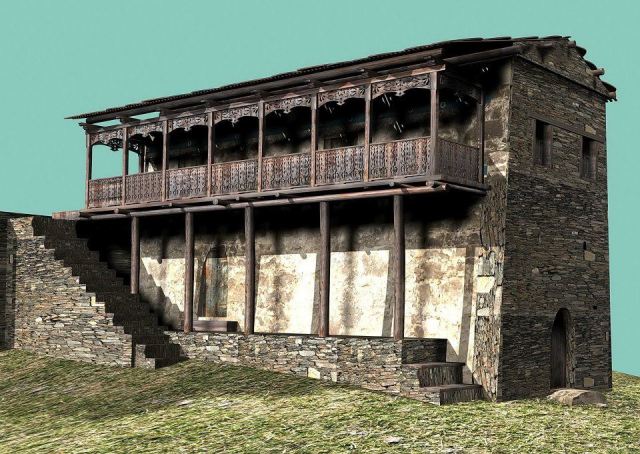

This tin home is where we stayed in Parsma in the summer of 2008. The view was spectacular and the home very comfortable. Parsma has this magnificent fortress which would have been used by the villages when threatened by attacks from neighbouring Dagestan

Parsma has this magnificent fortress which would have been used by the villages when threatened by attacks from neighbouring Dagestan

In this picture we can see one of the fortresses to be found in Parsma. These magnificent dry construction buildings would easily have kept enemies at bay. The door on the ground floor is very low indeed making it difficult for the attacked to enter.

Chigho is one of the most remote inhabited villages in Tusheti. Perched on the side of the mountain the trail from Shenako. Chigho makes for a breathtaking stopping off point to take in the magnificent landscape.Chigho has some excellent examples of fortified homes although due to their remote position many are in danger of deteriorating due to dwindling population .

I recently found this blog entry (2013) talking about the restoration of Dartlo village.

http://georgiaabout.com/2012/09/19/about-architecture-restoration-of-dartlo-village/

ABOUT ARCHITECTURE – RESTORATION OF DARTLO VILLAGE

Earlier this year the Municipal Development Fund of Georgia (MDF) launched a project to restore the vernacular architecture of the medieval village of Dartlo village in Tusheti. The initiative is part of a larger project, called “Kakheti Regional Development Project” that is developing tourism in Kakheti.

Dartlo village is one of the most beautiful villages in Tusheti. Situated 2000 meters above sea level in the Alazani River gorge it rests on the northern slope of the Greater Caucasus Mountains.

The project will repair many of the buildings in the village and restore traditional features, such as slate roofs.

There are three main types of dwellings in Dartlo: Traditional, Transitional and Modern. The traditional type, fortress-houses, have between 2-6 floors and an attached fortified tower. The transitional type of housing is similar to the traditional fortress-houses but often have roofed balconies and additional constructions for storage. This type is called “Karseani”.

The following photographs show what the buildings look like now and what they will look like after restoration.

Not a bad effort .Thanks to Giorgi Bakuridze for contributing this picture.

The follwing two images provided by Kakha Khimshiashvili are of Upper Omalo .They represent Omalo in the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century. One photo is date 1880 which is interesting . The first pictures were taken France in 1813 1816 . Modern photography began in the 1820s

Modern Upper Omalo looks very different from these pictures but the syle of buildings can be seen all over Tusheti .

Modern Upper Omalo looks very different from these pictures but the syle of buildings can be seen all over Tusheti .

Watch this space more to follow

The following pictures are for a new section on Architecture in Tusheti talking about churches and other topics Draft.

There appears to be around three types of religious architecture in Tusheti: pre-Christian (pagan), pagan-Christian (syncretic) and Christian.

Buildings that are pre-Christian architecture are called “Djvar-Khati”. These are often sacral, religious buildings made up from small-size constructions with towers, shelters for clergy and other building/shrines for religious rituals made out of shale/slate .

Monuments of syncretic architecture include small-size chapels from the medieval period. These constructions were often created for burials facing from west to east. Good examples can be found in Dartlo, Gudaanta, Tsaro.

Holy Trinity Church in Shenako built in the XX century . The only restored and fully working Georgian Orthodox church in Tusheti .

Holy Trinity Church in Shenako built in the XX century . The only restored and fully working Georgian Orthodox church in Tusheti .

This wonderful Christian church in the hamlet of Iliurta is now in very poor condition and infrequently used but it still provides a rare insight into vernacular chapel construction to be seen throughout Georgia .

The building top left is a chapel in Parsma, however I understand this predates the other Christian churches in Tusheti and is not used for Christian services and is most likely syncretic . It's used for festivals and as a result it plays a dual role as a chapel and a sacred place for animist.

.jpg) A pre-Christian shrine or Khati.

A pre-Christian shrine or Khati. An excellent example of a fortress in Parsma.

An excellent example of a fortress in Parsma.I've now run out of steam and information. If you have anything to add please let me know , I think this section has run its course.

Vernacular architecture is characterised by its reliance on needs, construction materials and traditions specific to its particular locality.

ReplyDelete